Global organizations seek local solutions

Editor's note

Today through Wednesday, the Daily Bruin is publishing a series about the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community in Malawi, a country that outlaws homosexuality and in which UCLA has a strong research presence. The reporting in Malawi was made possible by the Bridget O’Brien Scholarship Foundation, which is in its sixth year of funding UCLA journalism with global reach and local impact.

This year’s recipients, reporter Sonali Kohli and photographer Blaine Ohigashi, spent 24 days in Malawi talking to LGBT Malawians, activists and researchers about the health care and human rights challenges the community faces. The reporters provided meals and transportation for some sources who agreed to be interviewed. Most interviews were conducted in English, but some spoke in Chichewa, the most common language in Malawi. In those cases, the interviews were translated by a representative from the primary LGBT rights organization in the country. All of the LGBT men and women the journalists spoke to in Malawi were kept anonymous in this series because of the danger that the laws and heavy social stigma pose. The journalists asked each anonymous person to choose the name that appears in the stories.

Visit www.rememberingbridget.com to learn about the scholarship.

He lifted his shirt, revealing a stomach that was two different colors. Black spots covered a dark brown abdomen. Most of the itchy marks were concentrated there, but others speckled his arms and face.

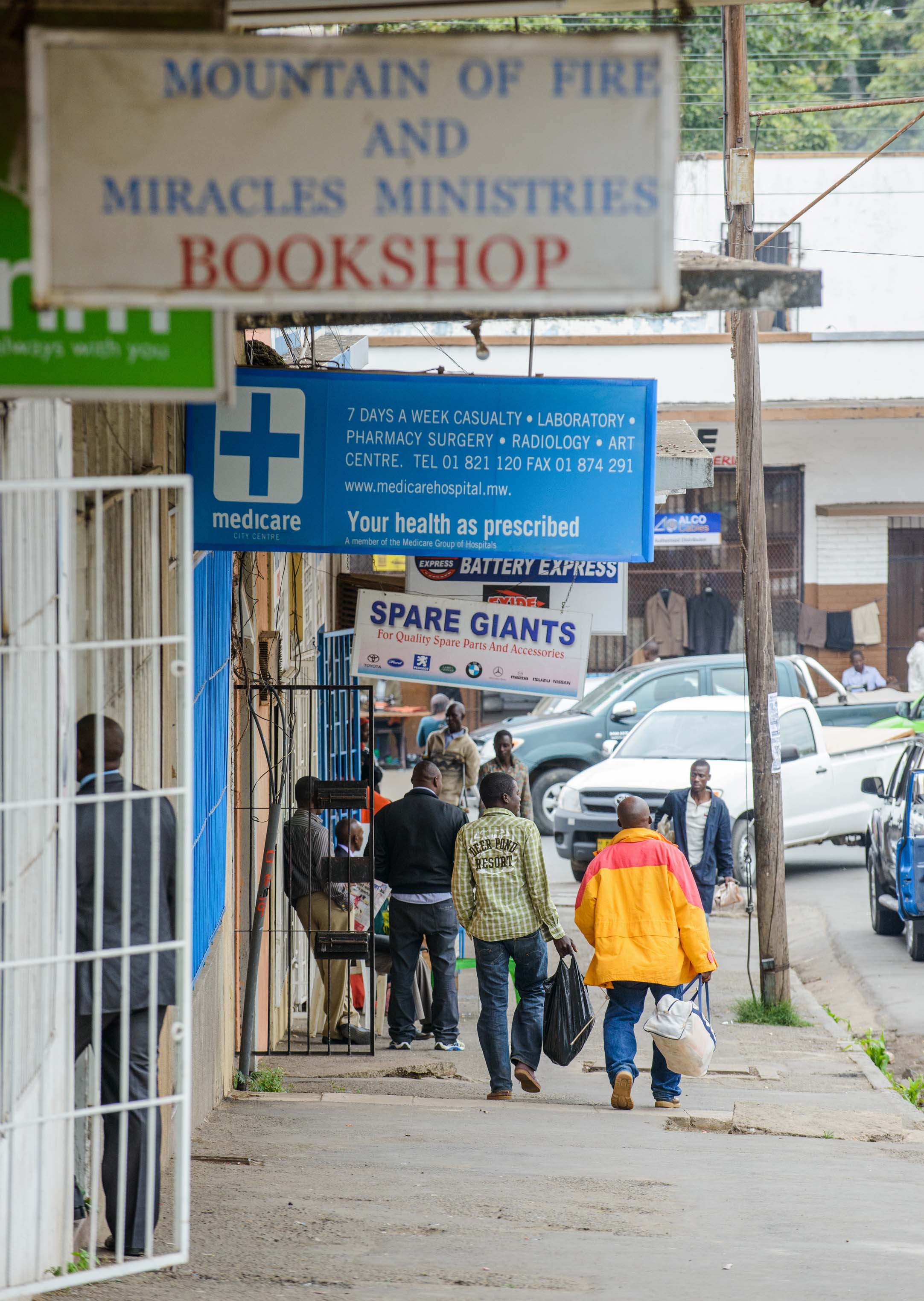

“They are all over,” he said, resting in the sunny food court of a Malawian strip mall. The spots were a negative reaction to a tuberculosis medication that the man, who asked to be called Chipo, had taken.

Fatima Zulu, who sat next to Chipo under an umbrella, stroked the marks on his left arm as they waited for their pizza.

“They were much worse,” she said. “They’ve gotten better over time, but they were much worse.”

Zulu is the community engagement coordinator at the Johns Hopkins University Research Project in Blantyre, Malawi, a southern city and the country’s economic capital. She oversees a clinic that conducts research on sexually transmitted diseases at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre.

Chipo is one of the patients she has helped. He is gay, and, as he found out a few years ago, HIV positive. Tuberculosis is the primary cause of death among HIV-positive patients, according to the World Health Organization.

The drugs did enough to help him regain some health. He returned to his job in advertising, but the spots remain.

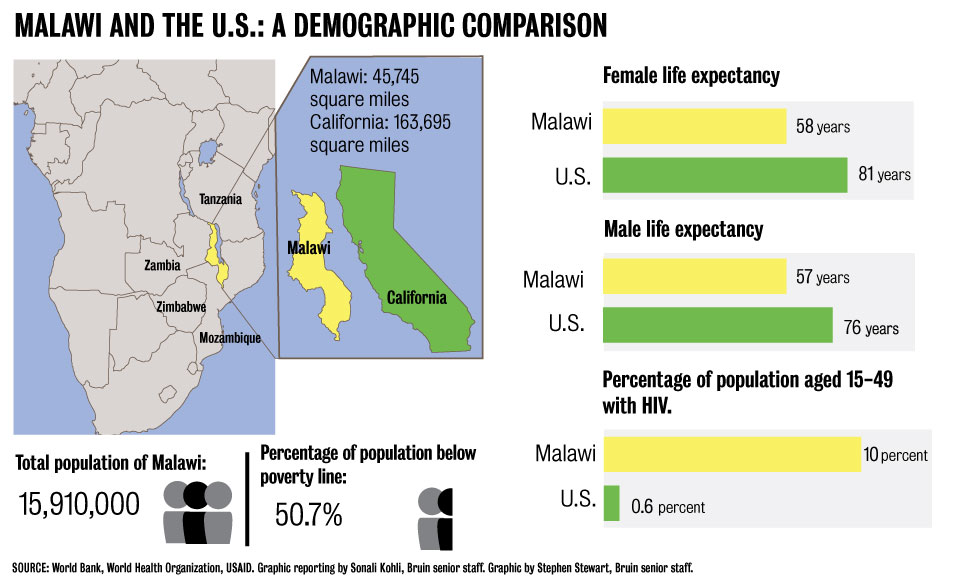

Malawi, a country smaller than the state of California, is tucked into southeastern Africa between Tanzania, Mozambique and Zambia.

Blantyre

The city of Blantyre is the commercial and financial center of Malawi, as well as the capital city of the southern region of the country. The city is densely populated and is home to many of Malawi’s universities.Lilongwe

Malawi’s capital and the country’s largest city, Lilongwe is located in the central region of the country. It is home to a maze of districts boasting bustling markets and houses most of the foreign diplomats in the country. The country celebrated its 49th year of independence on July 6, with performances and sporting events in the city.Mangochi

This area in the southern region of the country lies near Lake Malawi. Mangochi is home to many small fishing villages.Mulanje

Mulanje is a mountain town located in the southern region of Malawi, approximately 40 miles southeast of Blantyre. The town is known for its tea plantations and Mount Mulanje, with an elevation of over 9,800 feet.Mzuzu

Mzuzu is the capital city of Malawi’s northern region. The city is famous for its coffee.Zomba

Located in the southern region of Malawi, Zomba was the original capital of the country under British colonial rule. The lush, hilly city features the Zomba Plateau, which rises more than 5,900 feet above the city and the surrounding areas.It is also one of the 76 countries that outlaw homosexual acts, making it difficult for men who have sex with men to receive HIV treatment.

Men who have sex with men are referred to as “MSM” in medical circles. The term, meant to be apolitical, includes gay and bisexual men, as well as male sex workers and prisoners.

A 2008 population estimate of about 200 men in Blantyre showed that about 21 percent of men who have sex with men in that area were HIV positive.

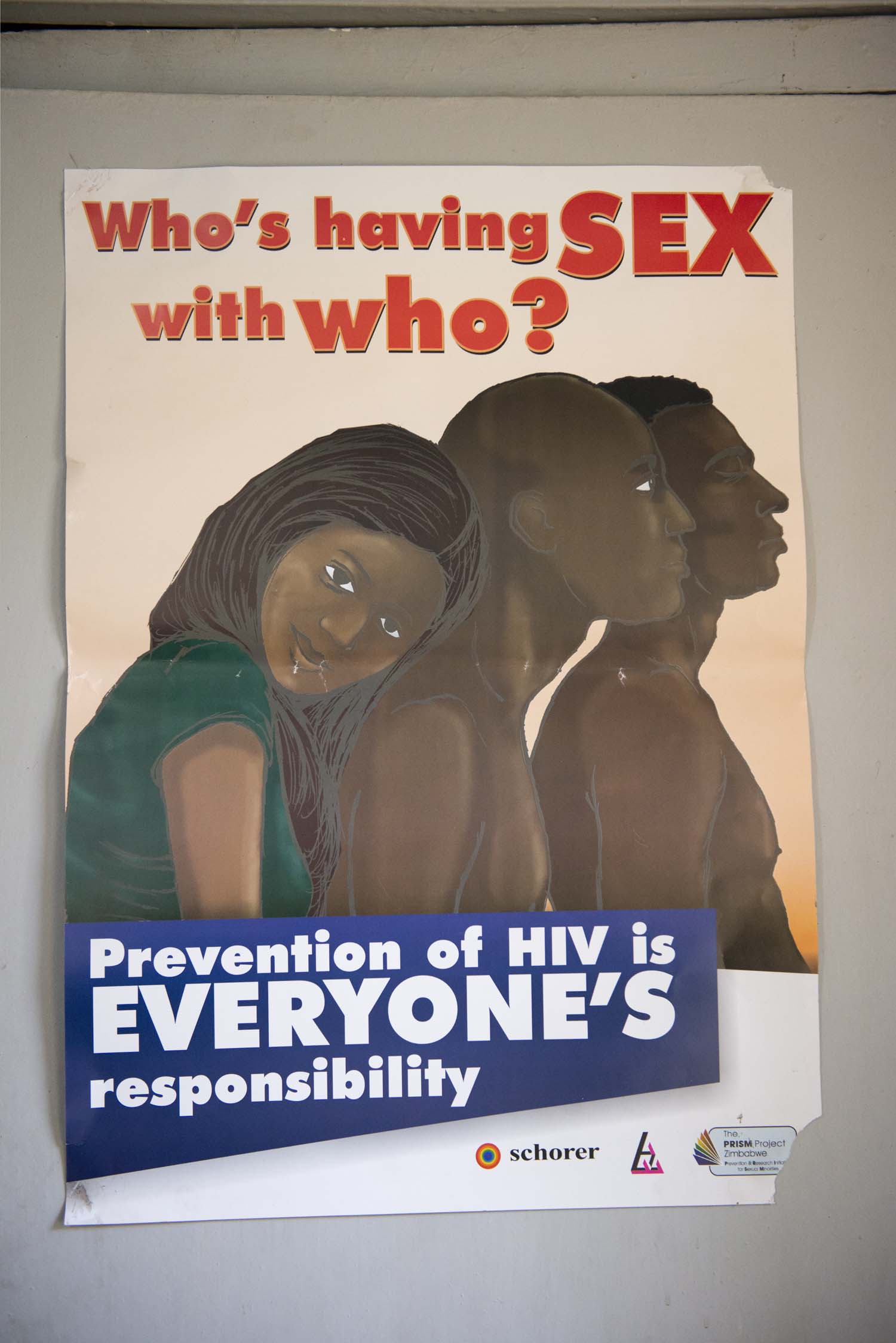

The Malawian government recognized for the first time about four years ago that MSM are a high-risk population for HIV contraction. Many of these men also have sex with women, which can spread the disease. Worldwide, MSM are 19 times more likely to have HIV than the general population.

But the Malawian government has done little to improve access to care for these men.

That’s partly because there’s a low acceptance of the gay community from a highly conservative, religious public, and because there is not enough nationwide data to prove that MSM play a significant role in the spread of HIV in Malawi.

Some doctors and activists from Malawi and around the world have stepped in, but most of the foreign organizations in the country – including UCLA – do not directly address this group.

MSM in Malawi who we spoke to said they are afraid of seeking medical treatment because they may be outed.

Consequences could include being disowned by a wife, church, friends or family, and, in rare cases, being arrested.

Several years ago, before he knew about his HIV status, Chipo sought treatment for a different rectal sexually transmitted disease. He thought that if he went to a private, internationally funded clinic, he would be well taken care of.

He was wrong.

“When I was coming from the consultation room, I found all the staff sitting in the lounge waiting to see me, saying that this boy is homosexual, that’s why he contracted the disease. When I was going out, people were peeping through the window, laughing,” Chipo said. The clinic was in Blantyre and was not affiliated with UCLA.

In a country of about 15 million, about 10 percent of the population aged 15-49 is HIV positive, according to World Health Organization statistics. That percentage is down from 14 percent in 2003, according to UNAIDS. This is partially because of internationally funded prevention efforts.

In Malawi, more than 90 percent of HIV/AIDS research, prevention and treatment funding is international.

As HIV prevalence decreases internationally, high-prevalence countries are seeing efforts to single out high-risk populations such as sex workers, drug addicts and MSM.

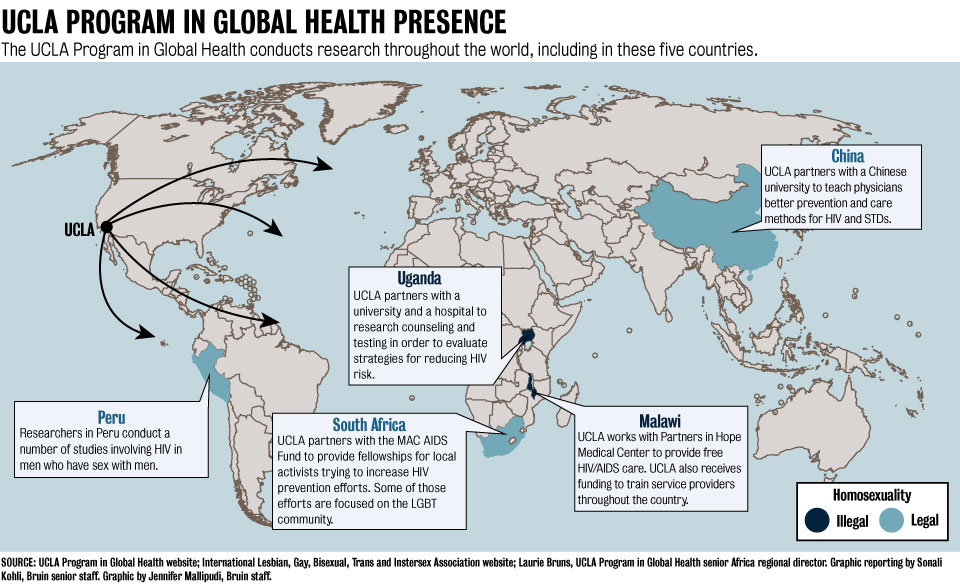

UCLA focuses research and medical aid on some of these populations in other parts of the world where there is often a more accepting legal climate.

Money comes from worldwide agencies including the the United Nations and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and from individual countries such as the U.S. and England. It gets parceled out to the many nongovernmental organizations that saturate the streets in jeeps adorned with agency logos, and to faith-based organizations such as Partners in Hope, a private hospital in Malawi that UCLA partners with to conduct medical research and provide HIV/AIDS training, prevention and treatment services.

Research and rights

The UCLA Program in Global Health does not tailor any of its research or treatment specifically toward the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community in Malawi, nor do most U.S. organizations operating in the country.

The university does, however, fund HIV/AIDS research and prevention efforts involving LGBT populations in countries such as South Africa and Peru, where homosexuality is legal.

Of the countries where UCLA conducts HIV/AIDS work, Malawi is one of the harshest toward gay men and women – men face up to 14 years in prison with hard labor if convicted of homosexual acts, and women face up to five years.

A current moratorium on enforcing the laws exists, but social stigma and the rare possibility of arrest still serve as barriers to medical care.

Although it is nationally and internationally acknowledged that MSM are a high-risk population, nonprofits and universities in the country have to be careful of addressing the issue for fear of alienation from the government and people they work with. Organizations say they could lose the support of the government and their local infrastructure if it seems like they are pushing other countries’ ideals in opposition to Malawi’s laws.

Malawi, though it has a secular government, is a mostly Christian nation in which anti-gay sentiment is high and people often refer to the Bible to reinforce their point that homosexuality is wrong.

Along the M1, the highway that spans the length of Malawi and serves as its main trade artery, a sign reading “Partners in Hope” greets drivers on their way into the country’s capital of Lilongwe. It leads to an expansive three-part medical center, founded by Dr. Perry Jansen, who was trained at UCLA.

UCLA works with the Christian medical center to provide private care, a free HIV/AIDS clinic, and training and research throughout the country.

The free HIV/AIDS wing is called the “Moyo Clinic” – Moyo means “life” in Chichewa, the most commonly spoken language in Malawi.

Partners in Hope and UCLA denied us access to the medical center, health care providers and patients for this series.

Before the trip, UCLA Vice Chancellor for Legal Affairs Kevin Reed wrote in a letter that “you will both make this trip at great personal risk to yourselves, and there is great concern within the UCLA administration that your project … will create undue risk for other persons as well as to UCLA programs operating in Malawi.”

John Hamilton, the clinic director for Partners in Hope and the head of the UCLA Program in Global Health in Malawi, refused to answer any questions when we went to Partners in Hope, because he needed approval to speak with us, and asked us to email questions instead. He then referred those questions to Jansen, the Partners in Hope founder and director, and Thomas Coates, the director of the UCLA Program in Global Health.

Jansen answered some questions via email. He wrote that the clinic welcomes all patients.

“(Partners in Hope’s) ethos is to consider all of our … patients worthy of our best,” Jansen wrote.

UCLA does conduct HIV/AIDS research in Malawi, as well as a clinical rotation program for UCLA medical residents. The university’s research and prevention efforts have focused largely on preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV, and UCLA receives funding through the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief on a project called “EQUIP-Malawi” to train and provide aid to local healthcare providers for better HIV/AIDS care.

But in other places, UCLA does tackle LGBT issues from a medical standpoint. In South Africa, where the LGBT community has full legal rights, the UCLA Program in Global Health partners with the MAC AIDS Foundation to provide local HIV prevention fellowships.

A number of the recipients focus on the LGBT community. One program near Capetown provides protection and legal aid for lesbian women who have been through “corrective rape,” the practice of raping lesbians in order to try to make them straight, while another in Johannesburg addresses the prevention needs of refugee male sex workers.

Meanwhile, the U.S. National Institute of Health is funding multiple UCLA Program in Global Health studies focusing on HIV prevention for MSM in Peru.

The difference between these countries and Malawi is the spectrum of legal rights. South Africa is, on paper, one of the world’s most LGBT-friendly countries, with legal rights built into the constitution. Human rights violations and hate crimes still happen in those countries, but a legal framework exists to protect the community.

Building a case

While UCLA’s approach to HIV/AIDS is similar to that of most international institutions operating in Malawi, other organizations do direct aid to the LGBT community.

Stefan Baral, a researcher at the Johns Hopkins Center for Public Health and Human Rights, has been working with the LGBT community in Malawi since about 2006. He works mostly with the Centre for the Development of People, known as CEDEP, Malawi’s primary gay rights organization.

But research in the country requires ethical approval from both the home institution and the host country.

Baral and CEDEP used a carrot-and-stick approach to get the Malawian Ministry of Health to support their research on HIV/AIDS prevention in MSM, Baral said.

He pointed out that more data on the MSM community in Malawi would increase the country’s eligibility for Global Fund money, which is increasingly becoming tied to human rights.

Baral also warned the ministry that to maintain their current funding levels, they needed to use data to demonstrate which populations are in need and develop specific plans.

The timing was convenient – the United Nations had recently asked countries to provide reports detailing their responses to AIDS in different categories. Some of those included prevalence, levels of condom use and HIV testing in MSM, and the government asked Baral to include those indicators in his surveys.

“It makes them look better, more responsive to the UN,” Baral said.

Malawian Minister of Health Catherine Hara did not respond to multiple email requests for comment about the country’s HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment strategy concerning MSM.

It was difficult to get the projects going, though. Baral had little luck approaching organizations and nonprofits who work with HIV/AIDS prevention in the country, because people said they did not want to jeopardize the rest of their work by touching such a contentious issue.

“People would meet with me because I’m from Johns Hopkins and I’m a physician,” Baral said. “But as soon as it got into a serious conversation about what we wanted to do and what we were there for, the conversation ended.”

Baral’s team and CEDEP leaders determined that in order to provide aid for the community, they must first prove there is an LGBT presence in Malawi, something many people still deny.

They started with a 60-person survey in 2006 to establish the existence of MSM in the country and ask about the community’s needs. Then they moved on to the 2008 population estimate in Blantyre, where about 21 percent of about 200 participants tested HIV positive. The 2008 study led to the first governmental acknowledgment of the LGBT community.

“The data ... was used to justify the inclusion of MSM in the national HIV strategic plan,” said Gift Trapence, CEDEP’s director.

But getting MSM in the national plan doesn’t mean that the government is actually allocating aid to that community.

So Baral and the center at Johns Hopkins are conducting a study with CEDEP to determine whether it would be possible to implement an intervention and prevention program for the MSM community in Malawi.

In 2010, the researchers took 100 HIV negative participants from the population estimate study and monitored them with HIV counseling and testing every three months, as well as contact with peer educators who provided communication, condoms and lubrication. They’re now in the analysis stage of that study.

CEDEP is also conducting a population estimate in the rest of the country, to provide a more complete view of the MSM community and HIV prevalence, which could also help improve aid. This should be done by the end of the year, Baral said.

With a tighter grasp on how to prevent HIV in general populations and increased concern about getting the greatest possible value for donor money, governments and agencies are expected to make a strong and specific case for funding, said Patrick Brenny, the former director for the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, or UNAIDS, in Malawi. Brenny was the director until August, when he moved to Tanzania.

“Malawians haven't had to make that case before," Brenny said.

A helping hand

Zulu, Chipo’s friend and the project coordinator for the Johns Hopkins University Research Project, has more personal reasons for helping the LGBT community.

Chipo and Zulu met in 2010, when she did a presentation to teach MSM about HIV transmission and safe sex.

Chipo didn’t know he could contract HIV from a male partner, let alone that he was at greater risk of contracting the disease than other people.

Zulu, who was already working for the Johns Hopkins University Research Project at the time, wanted to do the presentation because she had recently lost a friend to a sexually transmitted disease. He was gay and afraid to approach her for help.

“He did not tell me until he was on his deathbed,” Zulu said. “That pushed me to do something.”

She approached Trapence to create a workshop to teach MSM the risks of transmission and safe sex practices.

At the workshop, she explained that anal sex is more likely to lead to HIV transmission than vaginal sex because the lining of the anus is much thinner. She taught them that men should wear condoms when having sex with other men and should use lubricant to prevent the condom from breaking.

Zulu has also made an effort to train health care providers on how to treat MSM, but some are still averse to the idea, so she doesn’t push them.

“What we have agreed is we don’t want them to work against their beliefs … as long as they are nice to these guys when they come in the clinic.” Zulu said. “You don’t have to treat them – welcome them nicely, introduce them to the person that they want to see. And that has worked well for us.”

But she also holds trainings for other providers interested in treating MSM.

In Malawi, not every health care professional is a doctor. A range of classifications between doctor and nurse exist, depending on the level of training – it’s common for a clinical officer, the equivalent of a U.S. nurse practitioner, to have the highest rank in a clinic, without going through full medical school.

This creates medical gaps that Zulu tries to address.

A clinician or nurse might misdiagnose gonorrhea in the throat, for example – they don’t expect to see the STD there, so they treat it as a normal throat infection, prescribing the wrong medicine and exacerbating the problem. Studies show that untreated throat STDs can lead to throat cancers.

During the medical trainings, doctors and nurses who are willing to treat MSM are asked to give their names and contact information to the organizers, who can pass those names on to men who need treatment.

Zulu said CEDEP should do more to ensure that MSM know the resources available to them. Some health care providers who attended the trainings said they have treated few, if any, MSM since they gave their names for referral.

But other practitioners remain reluctant to provide targeted aid, or to publicize it.

At trainings, Zulu reminds doctors and nurses of the oath they took to help all people, regardless of who they are. If they say they are promoting illegal activity by treating MSM, leaders at the trainings point out that doctors treat criminals who come to the office from prisons.

That might be because men don’t know where to go for help or who to ask for, Zulu said.

Chipo’s routine when he comes to the clinic, for example, is different than that of other patients. Instead of waiting, he and his sister, who often accompanies him to the doctor, walk straight to the check-in desk and ask for Blessings, a clinician who has been trained in treating MSM.

He is more comfortable this way, and though the medical treatment is similar to other clinics, Chipo does not face the ridicule he has in the past, so he comes back with any ailments he has.

And if he doesn’t return for a while, Zulu will notice.

“She calls me checking on me, or she sees I am not around,” Chipo said. “She calls, ‘Why are you hiding, what’s going on, what’s keeping you busy?’”

Zulu already lost one friend who was afraid to confide in her. She doesn’t want to lose any more. ■