Connecting health and human rights

Editor's note

All of the gay and bisexual men in these stories were kept anonymous because of the danger that the laws and heavy social stigma against homosexuality pose in Malawi. The journalists asked each anonymous person to choose the name that appears in the stories.

They are tucked into residential neighborhoods, protected by high walls and gates, or hidden off of side streets – in these buildings Malawian men and women are free to tease each other about their latest crush, to declare their goals and hopes for the future of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender rights.

The offices of the Centre for the Development of People, the country’s primary gay rights organization, are one part of a calculated approach that activists are taking to increase rights for LGBT people in a country where homosexuality is not only illegal but heavily stigmatized.

Activists from the organization, also known as CEDEP, use HIV/AIDS funding to conduct research, education and health care for the LGBT community, while trying to convince the public and other stakeholders that there are health benefits to decriminalization.

CEDEP was founded in 2005 by a group of men who realized that there was no Malawian organization to help the LGBT community, especially in terms of HIV/AIDS care, said Gift Trapence, the organization’s director.

Malawi is a small country squeezed into southeastern Africa, and one of 76 countries worldwide that outlaws homosexuality. Men face up to 14 years of hard labor in prison for violating the law, and women face up to five years in prison.

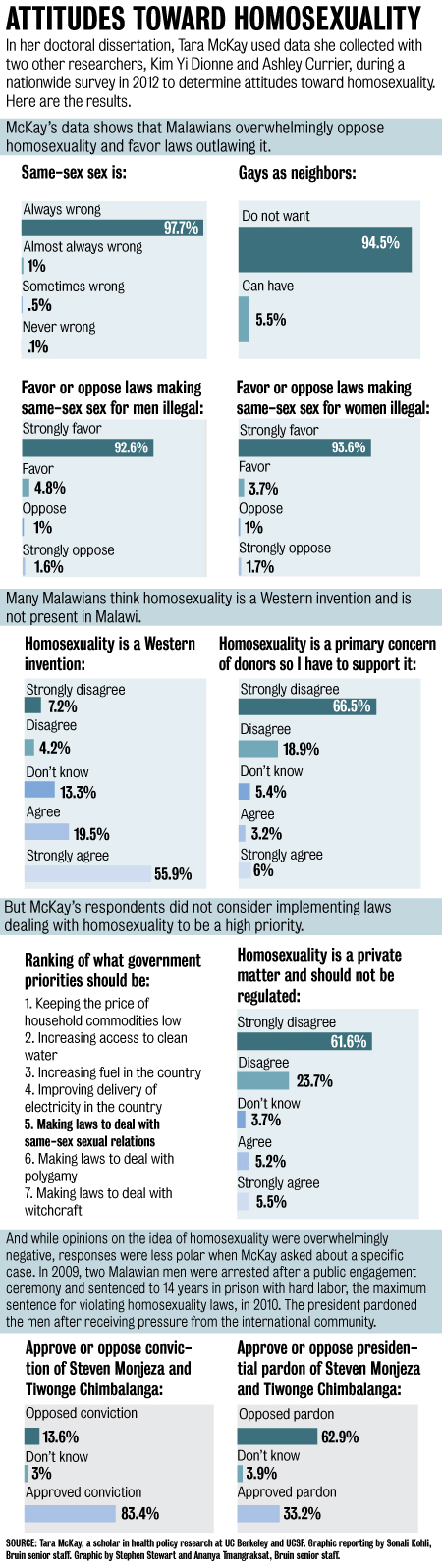

For her UCLA doctoral dissertation, sociologist Tara McKay conducted a nationwide survey in 2012 to determine Malawian attitudes toward homosexuality. McKay’s data shows that 97.7 percent of Malawians agreed with the statement “homosexuality is always wrong,” and more than 90 percent favor laws that criminalize same-sex sex.

But in a country where about 10 percent of the population is HIV positive, Malawi’s LGBT rights activists saw an opening in one of the most high-volume international donor streams: public health funding.

HIV/AIDS funding is increasingly becoming tied to prevention in high-risk populations, such as men who have sex with men. MSM is meant to be an apolitical term, used mostly in medical circles, to describe gay and bisexual men, as well as prisoners and male sex workers.

Countries which receive the most U.S. Government funding for HIV/AIDS

Homosexual acts are illegal in 10 of the 15 countries that receive the most HIV/AIDS funding from the U.S. Activists in some of the countries, including Malawi, use the funding to promote LGBT rights.- Imprisonment 14+ years

- Imprisonment up to 14 years

- Imprisonment, no length indication

- Homosexual acts legal

- Joint adoption by same-sex couples legal

HIV/AIDS funding from the U.S.

LGBT activists in other countries are using this argument as well – MSM worldwide are 19 times more likely to contract HIV than the general population, and many are also having sex with women in countries like Malawi where homosexuality is outlawed.

Plus, most people agree that everyone has a right to health services, said Patrick Brenny, who is a former Malawi director for the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, or UNAIDS. He was the Malawi director until July of this year, and moved to Tanzania in August.

“There is the public health approach that says anyone who needs a service should get it,” Brenny said. “And no one argues about that.”

The United States Agency for International Development committed $96.8 million in aid to Malawi during the 2013 fiscal year. Of that, the biggest chunk – $26.9 million – went to combatting HIV/AIDS.

An easy way for donors to measure the effects of their funding is through the clearly defined programs that organizations such as CEDEP implement.

For example, activists conduct population estimates to convince the government that MSM exist and need health care, and they host trainings that educate different societal groups, like church leaders and doctors, in an effort to change their perceptions about the LGBT community.

The government placed a moratorium on enforcement because Malawian president Joyce Banda asked parliament to review the laws against homosexuality, according to an email from Steven Nhlane, the president’s spokesman.

“The moratorium is to allow consultations to take place in an atmosphere that will encourage freedom of expression,” Nhlane wrote.

But public opinion is against a change.

When asked about what the government’s priorities should be, laws regarding homosexuality were low on the list for most Malawians, according to the survey from McKay’s UCLA doctoral dissertation. Respondents ranked it fifth out of seven priorities, in between “improving delivery of electricity in the country” and “making laws to deal with polygamy.”

It is somewhat rare to hear of an LGBT-related arrest, but members of the community say they still fear that police have the power to arrest them and could use the social stigma to intimidate them or extort bribes.

Most Malawians McKay surveyed said they would not want “homosexuals as neighbors.”

LGBT activists’ long-term goal is to eliminate social stigma against the LGBT community. They do recognize that the transition will be a slow one, and it will likely be many years until LGBT people are accepted.

But HIV/AIDS funding has potential human rights implications.

A vulnerable state

On an evening in June, two men finished their drinks at a local bar in northern Malawi.

It was like most bars in the country’s small towns and villages – the counter is large enough for a few people to stand by, and most patrons sit outside, surrounded by a makeshift fence of mismatched wooden sticks protruding from the ground.

It’s the kind of place where you can find people drinking at every hour, with company or completely alone, shelling out around 50 kwacha (about 15 U.S. cents) for a small, sealed plastic bag filled with clear liquid that’s 40 percent alcohol.

One of those men, who asked to be called Copro, told me his story in July. He spoke in Chichewa, the most common language in Malawi, and a representative from CEDEP translated.

The CEDEP representative took down Copro’s story as part of a project to document all human rights violations related to the LGBT community in the country. In 2015, the United Nations will conduct a review of human rights records in Malawi. The UN conducts these worldwide assessments periodically to determine what human rights issues need to be addressed and where.

The project to document gay rights violations in Malawi is a partnership between CEDEP and another Malawian human rights organization, the Centre for Human Rights and Rehabilitation. If the data reveals a pattern of discrimination, the review could help to increase focus on the LGBT community’s human rights concerns in the long run, instead of just HIV/AIDS needs.

As of July, Copro lived with someone who did not know Copro’s sexual orientation. So instead of taking his boyfriend home after the bar that night, they went to the house of his gay friend, who lives nearby and lets Copro use the house for sex when his boyfriend comes to visit, Copro said.

Around 8 p.m., they heard a loud banging on the door.

A group of community police officers had surrounded the house, Copro said. They broke in, catching Copro and his boyfriend having sex.

The officers forced both men to put their clothes on and took them to the station for the night, Copro said.

Copro’s arrest happened in a village in Malawi’s northern region, where community police officers are like a neighborhood watch and don’t necessarily follow the national discourse about whether to enforce sodomy laws. They take a case to the village’s or area’s chief, who decides whether to take it to the government-run police.

On the way to the chief the next morning, Copro’s friend intercepted them and bribed the officers by paying them each the Malawian equivalent of a few U.S. dollars for Copro’s release.

The community police told the two men that they were never to be seen together again. But they have met since the arrest, and in July they were still a couple.

A network of trust

Stories like Copro’s happen in remote places, and the only way that larger organizations like CEDEP find out is through the networks of peer educators – mostly gay men – that they have developed throughout the country.

These networks are often established using HIV/AIDS funding, because peer educators are tasked with spreading HIV/AIDS prevention messages. In the absence of open forums, they are the ones who often carry out programs that directly impact LGBT lives.

They meet in bars to discuss HIV prevention, they distribute free condoms and lubrication from CEDEP, they find MSM to participate in studies and gain access to services.

As of July, there were about 80 peer educators throughout the country.

Trapence said the peer education model is the most efficient way to connect one of the country’s most hidden populations, because the men already trust each other. They can pass information to former and current partners, or friends of those partners.

But the peer educators are volunteers, many unemployed, and they function on a very small stipend for communication and transportation, Trapence said.

Because the peer educators rely mostly on project-based funding from donors, it is difficult to implement long-term strategies through this program.

“This is volunteer work,” Trapence said. “You find that people end up using their own personal resources to reach out to their peers.”

No longer alone

Just the existence of a gay rights organization in the country affects some Malawian LGBT individuals, regardless of whether they benefit through HIV/AIDS prevention.

One gay man, who asked to be called Fortune for this story, works for CEDEP.

We met on a brisk July evening. He sat at a corner table by a hotel pool – he chose the spot for the interview because he wouldn’t see anyone he knew there, and no one would overhear.

Fortune remembered reading an article in an English-language magazine about gay men when he was 14.

He knew then that’s what he was.

At the time, he thought he was the only gay person in all of Malawi, he said. Two years later, he and a friend at his boarding school slept in the same bed and kissed.

They thought they were the only two gay people in the country.

The perception that homosexuality does not exist in Malawi is a common one, McKay said. Her data shows that more than 75 percent of Malawians either agreed or strongly agreed that “homosexuality is a Western invention.”

Fortune was fired from the Christian radio station where he worked from 2003 until 2006. He chose to be honest about his orientation when he was hired, and thus began three years of conversion efforts.

“They told me it’s very wrong to be a Christian and be gay at the same time,” Fortune said. “They told me to change.”

He tried exorcisms, hoping to rid himself of homosexuality.

Every Wednesday, Fortune went to pray on a mountain with a pastor.

He did a 41-day fast, foregoing food from 6 a.m. until 4 p.m.

“But it did not work.”

It wasn’t until 2007, when a friend invited him to a launch party for CEDEP, that Fortune realized how many men were like him.

“Some of the people who I didn’t expect to be gay were at that party. So I went to them and I asked them, ‘Are you sure you are gay?’ And they said, ‘Ah yes, this is how I am,’” Fortune said. “Some people I had met in the streets, but I didn’t know they were also gay.”

He was fired from another job in 2010, a nonprofit benefiting children, when the organization found out he was gay, he said.

He got a job with CEDEP assisting with HIV/AIDS prevention research and data collection.

Working closely with an LGBT organization does have its risks, though.

In May, someone posted a list of lesbian women in Malawi on Facebook, followed by a list of gay men that was released over three days.

“I was just praying that my name shouldn’t appear. Please, please, please, I was praying,” Fortune said. “But it appeared.”

Fortune, CEDEP leaders and others reported the page to Facebook, and it was shut down, but the lists popped up again within days.

Even though anti-gay laws are not strictly enforced in Malawi, the likelihood of them being revoked any time soon is extremely slim. No one wants to touch this controversial of a topic with a presidential election next year, Trapence said.

Legalizing homosexuality wouldn’t solve all the community’s problems, and it likely would not get rid of social stigma. But, Fortune said, it would help recognize gay men as equal to others.

Fortune told his story over the course of an hour, pausing whenever a waiter passed by. Bright red lights flooded the cafe behind him, but he spoke under a protective blanket of darkness. ■