Carrying an unrelieved burden

Editor's note

All of the LGBT men and women in these stories were kept anonymous in this series because of the danger that the laws and heavy social stigma pose in Malawi. The journalists asked each anonymous person to choose the name that appears in the stories.

The couple sat side by side in a Malawian coffee shop, both sets of arms crossed on top of the table, no parts of them touching.

One of the men, who asked to be called Pablo for this story, has been clean for a year – he credits that to his boyfriend of six years, who asked him to stop using drugs and drinking for the sake of their relationship.

Malawi is a small country tucked into southeastern Africa, between Tanzania, Mozambique and Zambia. Homosexuality is both illegal and heavily stigmatized, so Pablo and his boyfriend have to be cautious about the way they act in public. Most people assume they’re friends or cousins.

In Malawi, few resources exist to combat the underlying mental health problems that can lead to addiction for the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community.

Members of the LGBT community face higher rates of substance abuse than the general population worldwide because they tend to experience higher levels of stress, said Ilan Meyer, a UCLA law professor who has researched mental health within the LGBT community for the Williams Institute at UCLA, which conducts law and public policy research on the LGBT community.

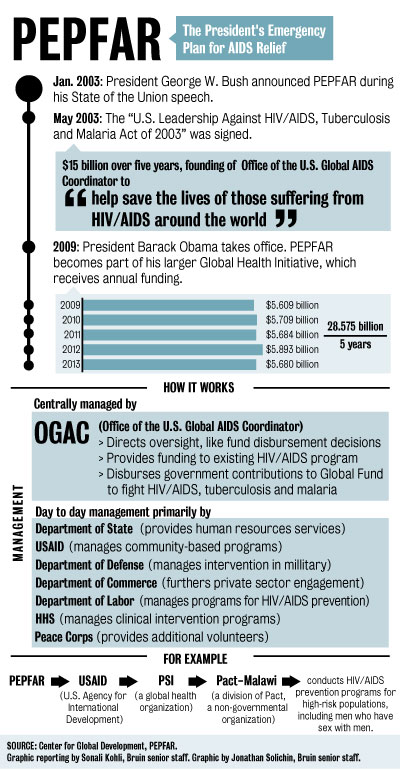

The United States Agency for International Development committed $96.8 million in aid to Malawi during the 2013 fiscal year. The biggest chunk of that – $26.9 million – went to combatting HIV/AIDS. None of it went to what is classified as “democracy, human rights and governance.”

Most of the funding to decrease addiction in the LGBT community is dedicated to preventing HIV/AIDS by stopping the drug and alcohol abuse that leads to risky sexual behaviors – not by addressing the psychological sources of that addiction.

As of July, there were only two licensed clinical psychologists in all of Malawi, said Chiwoza Bandawe, one of those psychologists and the dean of students at the University of Malawi College of Medicine.

Add to that limited funding, and the LGBT community is left with limited access to adequate mental health and counseling services, Bandawe said.

Looking for a safe place

Mental health resources for LGBT communities are greater in countries with more gay rights, such as the United States, Meyer said.

UCLA, for example, has an LGBT resource center centrally located on campus, near Bruin Plaza. It has an in-house counselor and a library. The university has had some form of an LGBT student center since 1995.

In Malawi, however, the LGBT community lacks a place where they can ask questions, find educational resources and seek counseling and legal aid, according to a needs assessment study by Bandawe and the Centre for the Development of People, the country’s primary LGBT rights organization, commonly referred to as CEDEP.

Without counseling, gay men and women are often alone in facing self-hatred and the threat of losing their jobs and families if found out. Some choose to try conversion attempts or exorcisms.

Constantly hiding their identity from families, friends and employers can take a mental toll on gay men and lesbian women and lead to a dependence on alcohol or drugs, Bandawe said.

Problems with addiction are only exacerbated by Malawi’s high unemployment rate and a drinking culture that starts in the morning and provides easy access to small plastic bags of 40 percent alcohol for the equivalent of about 15 U.S. cents.

“I would actually spend the whole night in the club, and I would drink too much whiskey,” Pablo said.

Pablo drank and went out because that’s how most of the men he surrounded himself with spent their time.

He was addicted.

He was able to stop because he had encouragement from his boyfriend and a supportive family in Zimbabwe, where the culture is more open toward homosexuality. Meanwhile, full-time employment at CEDEP keeps him busy so that he doesn’t spend his time drinking.

But after Pablo became sober, he noticed that some of his friends were still abusing.

One program Pablo is involved in with CEDEP includes a network of peer educators who share messages about HIV/AIDS prevention with the community, which mostly consists of men who have sex with men. Earlier this year, they taught that drug and alcohol abuse in an already high-risk community can make an easy transmission even easier because men who are consistently high or drunk might share needles or be more likely to have unprotected sex.

Pablo had pushed for this message.

“I’ve been clean since last year August. So I used an example of myself,” Pablo said. “If it’s working out for me, I thought it wise to spread it out to my friends.”

A friend of Pablo’s, who asked to be called Skinny, has an alcohol problem. Skinny in one of the peer educators responsible for spreading CEDEP’s quarterly messages. A one-on-one talk in Pablo’s office earlier this year helped him reduce his drinking, he said.

Skinny is a soft-spoken man in his early 20s, who laughs through any part of a conversation that makes him uncomfortable. As of July, he had a boyfriend for two years. He used to take a variety of drugs and drink 10 to 15 bottles of beer a night. Falling asleep at the bar was common, he said.

Skinny reduced his drinking habits before spreading the message, he said in July. Now he drinks four to five bottles of beer, but only on Saturdays.

He has also encouraged some of his clients to get clean. In July, he said some of them had started drinking less, but others had kept up their habits after talking to him.

“But as time goes maybe they’ll change, because we don’t just send the message once,” Skinny said.

So he’ll continue to bring it up in conversation – in the bars where he meets friends or when they come to him seeking the condoms and lubrication that CEDEP provides.

A deeper problem

Merely changing behavior, however, does not necessarily resolve the mental health issues that often lead to addiction. Members of Malawi’s LGBT community who have reduced their drug and alcohol usage still have to cope with the threat of arrest, the fear of being outed and the stress of constant hiding.

During a July focus group about drug and alcohol abuse at CEDEP’s northern office, men talked about the reasons behind substance abuse in the LGBT community.

It’s easier to approach a man romantically when you’re drunk – the alcohol takes away the fear of rejection, the fear of arrest, the fear of fighting with someone.

Many people are unemployed, alcohol is cheap and there’s nothing else to do.

Walking down the street is stressful when you know everyone is whispering about you, saying you’re gay, judging you.

But CEDEP does not currently have the funding to substantially expand mental health aid, CEDEP director Gift Trapence said in July.

“There is that gap that we’ve realized that we need to work on,” he said. “But of course now comes the issue of resources.”

Ideally, Trapence would like to be able to provide shelter to men and women who have been outed and kicked out of their homes, as well as counseling resources at the offices.

Lane, a gay Malawian man who asked to remain anonymous, didn’t have a professional to turn to this summer when his family found out he was gay.

In June, his upper middle-class family kicked him out of the house and fired him from the family business after they saw his name on a Facebook page outing him and other Malawians who are gay and lesbian.

His family found out where he was staying later that month and came to the house at night.

They drove him to his uncle’s house, pinned him to the ground and gagged him with a cloth. Then, his mother, sister and brothers beat him for four hours, he said.

“It was like a nightmare that I was trying to wake up from, but I realized it was a reality,” he said.

The only thing that makes remembering that night easier, Lane said, is to get high.

He uses pot two or three times a week, plus cocaine once every one or two weeks, when he can get his hands on it.

He’s hoping to get asylum in another country, so he can pursue his flight attendant career.

But he needs money to pay for that school. As of September, he was still $1,000 short.

“All I need is my life back,” Lane said. “I want to achieve what I’ve been looking forward to.”

Meanwhile, he said he would like access to a psychologist who can help him cope, to play the role that drugs do now.

Pablo, who works in the northern region of Malawi, would like to see the main room in the CEDEP northern office transformed into a library, a safe space where people can come to educate themselves on their rights and resources.

Right now, he said, he can only rely on his own experience to provide that help. And it’s not enough. ■

Contributing reports by Blaine Ohigashi, Bruin senior staff.